70 Am. U. L. Rev. F. 203 (2021).

* Professor of Law, Washington and Lee University School of Law. The Author thanks Josh Fairfield and Shaun Shaughnessy for their helpful comments.

Abstract

In his Article Facebook’s Speech Code and Policies: How They Suppress Speech and Distort Democratic Deliberation, Professor Joseph Thai argues that Facebook skewed public debate with a policy that exempted politicians from its content-based rules. This Response updates the reader on Facebook’s retreat from this policy and identifies some preliminary lessons from it. Between May 2020 and January 2021, Facebook moved away from its “light touch” regulation of politicians’ speech by employing strategies like labeling and down-ranking—and, eventually, removal of content. After the January 6, 2021 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, Facebook de-platformed President Trump altogether, putting a final end to the “hands off” policy and ushering in a new era in which, apparently, Facebook will more openly regulate politicians’ speech using curation strategies. The Response concludes that down-ranking is the next major front in the regulation of politicians’ speech.

Introduction

With his contribution to the American University Law Review’s May 2020 symposium Issue on social media and democracy, Professor Joseph Thai joined the growing ranks of legal experts who have called attention to intersections between Facebook’s speech regulation and its business interests.1See Joseph Thai, Facebook’s Speech Code and Policies: How They Suppress Speech and Distort Democratic Deliberation, 69 Am. U. L. Rev. 1641 (2020). In Facebook’s Speech Code and Policies: How They Suppress Speech and Distort Democratic Deliberation, Professor Thai argued that Facebook’s speech code—its Community Standards—shapes political discourse in the United States and warrants sustained scholarly study.2Id. at 1645. He focused in particular on Facebook’s policy of excluding “politicians” from its content-based rules.3Id. This approach, Professor Thai argued, “skews public debate by amplifying the expressive power of already dominant speakers in our society.”4Id. at 1642.

However, shortly after Professor Thai published his Article, circumstances changed. Facebook retreated from its policy of exempting politicians from content-based regulation; it added warning labels to politicians’ posts, employed curation strategies to limit their reach, and eventually removed some posts by politicians altogether.5Rachel Lerman & Craig Timberg, Bowing to Pressure, Facebook Will Start Labeling Violating Posts from Politicians. But Critics Say It’s Not Enough, Wash. Post (June 27, 2020, 11:47 AM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/06/26/facebook-hate-speech-policies. A main target of these changes was President Trump,6See infra notes 47–50 and accompanying text; see, e.g., Lerman & Timberg, supra note 5 (describing how Facebook changed its policy after much public criticism and an advertiser boycott challenging Facebook’s refusal to remove President Trump’s hate speech). whose posts between May 2020 and January 2021 continually tested Facebook’s resolve to maintain a “light touch.” After a mob seized the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021,7Lindsay Wise et al., ‘The Protesters Are in the Building.’ Inside the Capitol Stormed by a Pro-Trump Mob, Wall St. J. (Jan. 6, 2021, 11:53 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-protesters-are-in-the-building-inside-the-capitol-stormed-by-a-pro-trump-mob-11609984654?mod=article_inline. Facebook first suspended President Trump’s account,8Sarah E. Needleman, Facebook Suspends Trump Indefinitely amid Pressure on Social Media to Clamp Down, Wall St. J. (Jan. 7, 2021, 8:37 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/president-trump-to-regain-ability-to-tweet-from-his-personal-twitter-account-11610032898 (reporting that President Trump’s ban was initially set to last twenty-four hours). then shut it down indefinitely.9Id. As of this writing, President Trump is prohibited from posting on Facebook, a complete reversal of the company’s original insistence that it would “protect political speech” by exempting politicians from its content-based rules.10Response to Biden Campaign, Facebook (June 11, 2020), https://about.fb.com/news/2020/06/response-to-biden-campaign [https://perma.cc/99UH-4R5B]; see Nick Clegg, Facebook, Elections and Political Speech, Facebook (Sept. 24, 2019), https://about.fb.com/news/2019/09/elections-and-political-speech [https://perma.cc/67SH-5J3E] (declaring that Facebook will generally exempt politicians’ speech from its normal content standards under its newsworthiness exemption). Facebook has referred its decision to de-platform President Trump to its Oversight Board, which operates as a sort of private “Supreme Court” that reviews the company’s speech-regulating decisions.11See Evelyn Douek, “What Kind of Oversight Board Have You Given Us?”, U. Chi. L. Rev. Online (May 11, 2020), https://lawreviewblog.uchicago.edu/2020/05/11/fb-oversight-board-edouek [https://perma.cc/UDN5-HPM5]. Some commentators believe the Oversight Board is likely to overturn the ban and restore the former president’s account12See, e.g., Paul Barrett, Facebook’s New Board Has Incentives to Bring Back Donald Trump, Bloomberg (Mar. 23, 2021), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-03-23/trump-s-facebook-ban-will-likely-be-overturned-by-new-oversight-board.; in its first five rulings, in January 2021, the Board overturned four of the company’s decisions to take down content.13See Kelvin Chan & Barbara Ortutay, Facebook Panel Overturns 4 Content Takedowns in First Ruling, apnews.com (Jan. 28, 2021), https://apnews.com/article/facebook-oversight-board-ruling-c6f6b20a4a6d5a208cebaa143412d3e5.

Building on Professor Thai’s thesis that a pressing need exists for further study of Facebook’s speech regulation,14See Thai, supra note 1, at 1645. this Response extends his account of Facebook’s treatment of politicians’ speech before and after the 2020 election. It argues that scholars should pay attention to the company’s rapid abandonment of its professed commitment to exempt politicians’ speech from content-based regulation. Though the retreat could evidence incompetence inside the company, I argue that it is better understood as a story about a corporate actor behaving the way that we should expect a corporate actor to behave: articulating “values” when doing so has public relations value, and moving away from those values when the gravitational pull of the company’s profit motive reorients. Facebook’s original choice to publicly announce an exemption for politicians protected its access to users’ data and worked to appease the elected officials who held power over it.15See id. at 1686 (“Facebook’s content moderation . . . mitigate[d] the pressure Facebook face[d] from powerful politicians. . . .”). That choice may even have protected the company from charges that its curation policies produced the equivalent of in-kind campaign contributions to one candidate or another in an election.

Facebook’s choice to backtrack from the policy, and to employ curation techniques that obscured this choice early on, was also driven by its profit motive.16See Lerman & Timberg, supra note 6 (describing how a boycott by large corporate advertisers—including Verizon, Hershey, and Unilever—harmed Facebook’s stock price). The sensitivity of the company to President Trump’s ebbing political power, and to public opinion, are evident as the story progresses. Do for-profit companies possess free speech values? Does Facebook? Facebook’s rapid tack away from its professed values suggests the answer.

I. Facebook Walks Back Its Hands-Off Approach

When Professor Thai published his Article in May 2020, Facebook was still asserting that it would not apply its content-based speech rules to politicians, citing free speech grounds.17Thai, supra note 1, at 1679; see also Cecilia Kang & Mike Isaac, Defiant Zuckerberg Says Facebook Won’t Police Political Speech, N.Y. Times (Oct. 21, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/17/business/zuckerberg-facebook-free-speech.html (reporting on Mark Zuckerberg’s reluctance to have Facebook regulate politicians’ speech). Although the company specifically advanced this position with reference to the upcoming November 2020 U.S. elections, it would soon pivot. Closer to the election, in the middle of a pandemic and an upsurge in misinformation about public health and election fraud, Facebook ended its “hands-off” approach to politicians’ speech.18See, e.g., Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook (June 26, 2020), https:// www.facebook.com/zuck/posts/10112048980882521 [https://perma.cc/DV8L-2736] (announcing Facebook’s new policies to regulate speech in advance of the 2020 U.S. election, including politicians’ speech). After President Trump and others used social media to foment political violence19See Wise et al., supra note 7 (describing President Trump’s conduct before and during the violent attack on the Capitol). and an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol ended in five deaths,20Jack Healy, These Are the 5 People Who Died in the Capitol Riot, N.Y. Times (Jan. 11, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/11/us/who-died-in-capitol-building-attack.html. Facebook shut down President Trump’s account, ending his ability to speak on its platform.21Mike Isaac & Kate Conger, Facebook Bars Trump Through End of His Term, N.Y. Times (Jan. 8, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/07/technology/facebook-trump-ban.html. A brief sketch of this chronology follows.

Facebook’s first step back from its policy exempting politicians from content rules came in March 2020 and concerned a politician outside the United States: Jair Bolsonaro, the president of Brazil.22See Josh Constine, Facebook Deletes Brazil President’s Coronavirus Misinfo Post, Tech Crunch (Mar. 30, 2020, 8:39 PM), https://techcrunch.com/2020/03/30/facebook-removes-bolsonaro-video [https://perma.cc/M28U-F94P]. That month, Bolsonaro attended a dinner with President Trump at Mar-a-Lago and returned home with a box of hydroxychloroquine.23See David D. Kirkpatrick & José María León Cabrera, How Trump and Bolsonaro Broke Latin America’s COVID-19 Defenses, N.Y. Times (Feb. 7, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/27/world/trump-bolsonaro-coronavirus-latin-america.html (noting that twenty-two individuals in Bolsonaro’s delegation tested positive for COVID-19 after the trip). Before the month was over, Facebook had removed content posted by Bolsonaro in which he touted hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 cure.24See Constine, supra note 22 (explaining that by removing Bolsonaro’s post, “Facebook ha[d] diverted from its policy of not fact-checking politicians”); see also Jeff Horwitz, Facebook Removes Trump’s Post About Covid-19, Citing Misinformation Rules, Wall St. J. (Oct. 6, 2020, 4:13 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/facebook-removes-trumps-post-about-covid-19-citing-misinformation-rules-11602003910 (discussing Facebook’s efforts to moderate COVID-19 misinformation). Twitter also deleted a tweet promoting hydroxychloroquine by Rudolph Giuliani, a Trump political surrogate, around the same time.25See Tom Porter, Twitter Deleted a Tweet by Rudy Giuliani for Spreading Coronavirus Misinformation, Bus. Insider (Mar. 29, 2020, 6:14 AM), https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-twitter-deletes-giuliani-tweet-for-spreading-misinformation-2020-3 [https://perma.cc/93JR-U3Y5]. Roughly a week before these first take-downs, an Arizona couple had been sickened—and the husband had died—after ingesting chloroquine phosphate, a chemical used to clean fish tanks.26See Coronavirus: Man Dies Taking Fish Tank Cleaner as Virus Drug, BBC (Mar. 24, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/52012242 [https://perma.cc/8BLR-LMS8]. The pair had taken the chemical after watching a press briefing in which President Trump touted hydroxychloroquine as a COVID-19 cure.27Id.

In May, Facebook took steps to limit the reach of a paid political ad by an anti-Trump group of Republicans, the Lincoln Project.28See Steven Levy, Why Facebook Censored an Anti-Trump Ad, Wired (May 15, 2020, 9:00 AM), https://www.wired.com/story/plaintext-why-facebook-censored-an-anti-trump-ad [https://perma.cc/L9ZA-CDB8] (reporting that the Lincoln Project’s political advertisement attributed multiple grim COVID-19 statistics to President Trump’s failings). It labeled the ad “partly false,” and downranked its circulation when users shared it.29Id. Yet a Facebook spokesperson told Wired magazine that Facebook would have treated the ad differently if it had come from a politician rather than an outside group.30Id. Later that month, Facebook refused calls to take down a post by President Trump that referenced the Black Lives Matter protests and warned, “when the looting starts, the shooting starts.”31The post, dated May 28, 2020, is available here: Donald J. Trump, Facebook (May 28, 2020), https://www.facebook.com/DonaldTrump/posts/i-cant-stand-back-watch-this-happen-to-a-great-american-city-minneapolis-a-total/10164767134275725. The phrase, “when the looting starts, the shooting starts” was the precise language famously used in 1967 by Miami police chief Walter E. Headley to threaten the Black community there. Tough Miami Policy Angers Negroes, N.Y. Times, Dec. 28, 1967, at 21 (quoting Headley as stating: “We don’t mind being accused of police brutality. . . . They haven’t seen anything yet”); see also Todd Spangler, Mark Zuckerberg Says Trump’s Inflammatory ‘Looting and Shooting’ Comment Doesn’t Violate Facebook Policy, Variety (May 30, 2020, 6:28 AM) https://variety.com/2020/digital/news/zuckerberg-trump-looting-shooting-facebook-policy-1234620960 [https://perma.cc/X8QR-UKDF]. President Trump had posted identical language on Twitter, which—like Facebook—allowed him to violate its content rules.32See Scott Rosenberg, Platforms Give Pols a Free Pass to Lie, Axios (Oct. 20, 2019), https://www.axios.com/facebook-twitter-social-media-politicans-misinformation-54703286-a674-4277-92c9-600bf28142f0.html [https://perma.cc/A938-NC3V] (reporting that Twitter could leave politicians’ posts up because of their “newsworthiness”). Twitter left the post up but affixed a warning label that covered the offending language.33See Todd Spangler, Twitter Adds Warning Label to Donald Trump’s Tweet About Shooting Protesters in Minneapolis, Saying It Glorifies Violence, Variety (May 29, 2020, 12:34 AM), https://variety.com/2020/digital/news/twitter-donald-trumps-warning-label-minneapolis-glorifies-violence-1234619685 [https://perma.cc/DZW5-7JYL]; Kate Conger, How Twitter and Facebook Plan to Handle Trump’s Accounts when He Leaves Office, N.Y. Times (Nov. 17, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/17/technology/how-twitter-and-facebook-plan-to-handle-trumps-accounts-when-he-leaves-office.html (“During Mr. Trump’s time as a world leader, Twitter allowed him to post content that violated its rules. . . .”); Kate Conger, Twitter Had Been Drawing a Line for Months when Trump Crossed It, N.Y. Times (June 23, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/30/technology/twitter-trump-dorsey.html. Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s CEO, stated that Facebook had chosen to leave the post up without a label because “the National Guard references meant we read it as a warning about state action, and we think people need to know if the government is planning to deploy force.”34See Spangler, supra note 31 (quoting Mark Zuckerberg). Thus, Facebook’s reasoning seemed to turn on President Trump’s position as an elected official, rather than his inclusion in the broader category of “politician.”

The following month, in June, Facebook took down posts and ads from the Trump campaign that showed an upside-down red triangle, a symbol used by Nazis—the first instance in which Facebook removed speech from the Trump campaign.35See Bobby Allyn, Facebook Removes Trump Ads with Symbol Used by Nazis. Campaign Calls It an ‘Emoji’, Nat’l Pub. Radio (June 18, 2020, 2:58 PM), https://www.npr.org/2020/06/18/880377872/facebook-removes-trump-political-ads-with-nazi-symbol-campaign-calls-it-an-emoji [https://perma.cc/SCC9-93MH]. The ads were paid speech, which might have justified different treatment.36See Clegg, supra note 10 (stating that the newsworthiness exemption does not apply to ads). However, at the end of the month, Facebook’s executives were still claiming that the platform regulated President Trump’s speech, if at all, with a “light touch.”37See Nick Clegg, Facebook Does Not Benefit from Hate, Facebook (July 1, 2020), https://about.fb.com/news/2020/07/facebook-does-not-benefit-from-hate [https://perma.cc/TLM9-B44J] (“We understand that many of our critics are angry about the inflammatory rhetoric President Trump has posted on our platform and others, and want us to be more aggressive in removing his speech. As a former politician myself, I know that the only way to hold the powerful to account is ultimately through the ballot box.”). “There is an election coming in November[,]” Facebook asserted, “and we will protect political speech, even when we strongly disagree with it.”38Response to Biden Campaign, supra note 10.

In July, in an extension of its both-sides approach, Facebook began adding labels to posts by both President Trump and presidential candidate Joseph Biden Jr., including one added to a President Trump post alleging a connection between mail-in voting and “#RIGGEDELECTION.”39See David Shepardson & Elizabeth Culliford, Facebook Places Label on Trump’s Post About Mail-in Voting, Reuters (July 21, 2020, 11:00 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-facebook-trump/facebook-places-label-on-trumps-post-about-mail-in-voting-idUSKCN24M24H [https://perma.cc/4REA-GPAS]. The label linked to a U.S. government website about voting.40See id. The move, apparently meant to redirect users to additional information, renewed an unsuccessful approach that Facebook used in 2017 and 2018, in which the company had pushed “Related Articles” to readers to counter false information.41See Sarah C. Haan, Facebook’s Alternative Facts, 105 Va. L. Rev. 18, 26–31 (2019) (explaining that while “Related Articles” originally began to post similar content, it changed into a fact-checking tool).

At the end of July, Breitbart posted a forty-three-minute video to Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube that made false claims about the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19.42See Jon Passantino & Oliver Darcy, Social Media Giants Remove Viral Video with False Coronavirus Claims that Trump Retweeted, CNN (July 28, 2020, 5:34 PM), https://www.cnn.com/2020/07/28/tech/facebook-youtube-coronavirus/index.html [https://perma.cc/7GSC-Q689]. The New York Times wrote that “the video had been designed specifically to appeal to internet conspiracists and conservatives eager to see the economy reopen, with a setting and characters to lend authenticity.” Sheera Frenkel & Davey Alba, Misleading Virus Video, Pushed by the Trumps, Spreads Online, N.Y. Times (July 28, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/28/technology/virus-video-trump.html (reporting that the individuals spreading misinformation in the video referred to themselves as “America’s Frontline Doctors,” wore white medical coats, and spoke in front of the Supreme Court). It attributed one of the earliest copies of the video that appeared online to a YouTube channel associated with the “Tea Party Patriots.” Id.; see also EJ Dickson, Fox News’ Best COVID-19 Truthers Unite to Promote Trump’s Favorite Drug, Rolling Stone (July 28, 2020, 4:45 PM), https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/americas-frontline-doctors-hydroxychloroquine-breitbart-donald-trump-103492 [https://perma.cc/KQT8-D8BC] (reporting that the Breitbart video was forty-three-minutes long). President Trump and his son, Donald Trump Jr., both amplified the video on social media by retweeting it and sharing links to it.43See Rachel Lerman et al., Twitter Penalizes Donald Trump Jr. for Posting Hydroxychloroquine Misinformation amid Coronavirus Pandemic, Wash. Post (July 28, 2020, 6:18 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/07/28/trump-coronavirus-misinformation-twitter. Within days, all three platforms had removed the video.44See Passantino & Darcy, supra note 42. However, before they pulled it down, the video was viewed more than 17 million times on Facebook alone.45See Christopher Giles et al., Hydroxychloroquine: Why a Video Promoted by Trump Was Pulled on Social Media, BBC (July 28, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/53559938 [https://perma.cc/D4XZ-6CQ5]. Twitter required the President’s son, Donald Trump Jr., to delete a tweet in which he shared the viral video and suspended him for twelve hours. Davey Alba, Twitter Limits Donald Trump Jr.’s Account After He Shares Virus Misinformation, N.Y. Times (July 28, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/28/business/twitter-limits-donald-trump-jrs-account-after-he-shares-virus-misinformation.html. It also removed tweets by President Trump in which the President retweeted other posts linking to the video. Id.; Lerman et al., supra note 43. Just a few days later, Facebook took down a post by the Trump campaign that embedded a video claiming children were “virtually immune” to coronavirus.46See Cecilia Kang & Sheera Frenkel, Facebook Removes Trump Campaign’s Misleading Coronavirus Video, N.Y. Times (Jan. 7, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/05/technology/trump-facebook-coronavirus-video.html.

In September, Facebook took down advertisements from the Trump campaign claiming that an influx of refugees to the United States would exacerbate the COVID-19 pandemic.47See Jo Ling Kent & David Ingram, Facebook Removes Trump Ads on Refugees and Covid-19, NBC News (Sept. 30, 2020, 5:58 PM), https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/facebook-removes-trump-ads-refugees-covid-19-n1241602 [https://perma.cc/FJM8-64UF]. It also announced new limits on politicians’ speech related to the election.48See Graham Kates, Facebook Says It Will Reject Political Ads Claiming Election Victory Before Results Are Declared, CBS News (Sept. 24, 2020, 1:56 PM), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/facebook-ban-political-ads-claim-victory-before-election-results [https://perma.cc/CH8N-8AFY] (describing Facebook’s changes in its policies concerning political advertising concerning the results of the election). It said it would ban election ads from the campaigns for a week leading up to the November 3 election, and that it would “reject[] political ads that claim victory before the results of the 2020 election have been declared.”49Id. (quoting Facebook spokesperson Andy Stone). Although it may have appeared at this point that Facebook was singling out politicians’ paid speech (campaign ads) for regulation, the company intensified its regulation of President Trump’s speech the following month, in October, when it removed a post by President Trump that falsely stated that seasonal flu was more dangerous to most people than coronavirus.50See Horwitz, supra note 24.

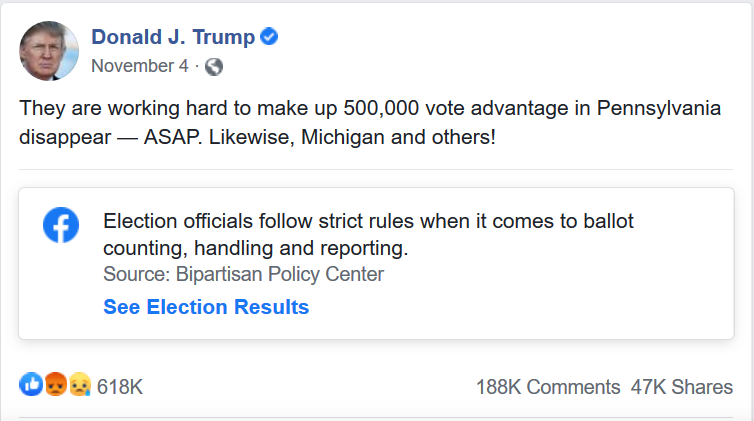

The U.S. presidential election took place on November 3, 2020; Democrat Joseph Biden Jr. won the popular vote by more than seven million votes.51See Mark Sherman, Electoral College Makes It Official: Biden Won, Trump Lost, AP News (Dec. 14, 2020), https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-270-electoral-college-vote-d429ef97af2bf574d16463384dc7cc1e. Immediately after the election, President Trump began posting content that suggested fraud was tainting the counting of votes. Facebook began labeling posts like the one authored by President Trump below.

Journalist Charlotte Klein argued in Vanity Fair that such warning labels “are basically doing nothing to slow the spread of false content” online and decried the company’s “incompetence” at handling post-election disinformation.53Charlotte Klein, Facebook Puts a Label on Trump’s Lies, Calls It a Day, Vanity Fair (Nov. 17, 2020), https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2020/11/facebook-misinformation-labels-not-working-trump [https://perma.cc/4BDF-KKUC].

On December 2, 2020, a day after Attorney General William P. Barr announced that the Justice Department had found no significant voting fraud in the 2020 election,54Katie Benner & Michael S. Schmidt, Barr Acknowledges Justice Dept. Has Found No Widespread Voter Fraud, N.Y. Times (Dec. 14, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/01/us/politics/william-barr-voter-fraud.html. President Trump used social media to distribute a “rambling” video that he had recorded in the White House.55Michael D. Shear, Trump, in Video from White House, Delivers a 46-Minute Diatribe on the ‘Rigged’ Election, NY Times (Dec. 2, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/02/us/politics/trump-election-video.html; see Chris Megerian, Trump’s Going out as He Entered: Amid Self-Induced Chaos, L.A. Times (Dec. 2, 2020, 3:35 PM), https://www.latimes.com/politics/story/2020-12-02/trump-self-induced-chaos (describing the setting of President Trump’s video). Barr resigned as Attorney General a few days later. See Katie Benner, William Barr Is out as Attorney General, N.Y. Times (Dec. 14, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/14/us/politics/william-barr-attorney-general.html. The video captured a long speech that President Trump described at the beginning as “possibly the most important speech I’ve ever made,” and in which he asserted, “[t]his election was rigged. Everybody knows it.”56Donald J. Trump, Statement by Donald J. Trump, The President of the United States, Facebook (Dec. 2, 2020) [hereinafter President Trump’s Facebook Statement], https://www.facebook.com/DonaldTrump/posts/10165908467175725. He asserted that “[i]f we don’t root out the fraud, the tremendous and horrible fraud that’s taken place in our 2020 election, we don’t have a country anymore.” Id. The video has since been removed from Facebook but remains available in its entirety on YouTube. Factbase Videos, Speech: Donald Trump Makes an Unscheduled Pre-Recorded Speech on the Election—December 2, 2020, YouTube (Dec. 2, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RFzTuaVS8Kk&t=4s. The New York Times described the video as “one falsehood after another about voting irregularities in swing states, attacks on state officials and signature verifications, and false accusations against Democrats.”57Shear, supra note 55. The Washington Post called it “an astonishing 46-minute video rant filled with baseless allegations of voter fraud and outright falsehoods in which he declared the nation’s election system ‘under coordinated assault and siege’ and argued that it was ‘statistically impossible’ for him to have lost to President-elect Joe Biden.” Philip Rucker, Trump Escalates Baseless Attacks on Election with 46-Minute Video Rant, Wash. Post (Dec. 2, 2020, 8:00 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-election-video/2020/12/02/f6c8d63c-34e8-11eb-a997-1f4c53d2a747_story.html. The Los Angeles Times wrote that the President “unspooled a series of debunked conspiracy theories about the election . . . .” Megerian, supra note 55; see also Andrew Restuccia & Alex Leary, Trump Reasserts Fraud Claims Despite Lack of Evidence, Losses in Court, Wall St. J. (Dec. 2, 2020, 5:55 PM), https://www.wsj.com/articles/trump-reasserts-fraud-claims-despite-lack-of-evidence-losses-in-court-11606949718 (describing the video as the “latest rhetorical escalation by the president”). Notably, although the video showed the President of the United States speaking in what appeared to be his official capacity—standing behind a lectern in the White House—its production values undercut its authenticity. No audience was seen or heard, he did not take any questions, and cuts in the video suggested some edits.58See generally Douglas Walton, What Is Propaganda, and What Exactly Is Wrong with It?, 11 Pub. Affs. Q. 383, 396, 398–400 (1997) (discussing common characteristics of propaganda); Emma Grey Ellis, How to Spot Phony Images and Online Propaganda, Wired (June 17, 2020, 7:00 AM), https://www.wired.com/story/how-to-spot-fake-images [https://perma.cc/JYH3-73HG] (elaborating on characteristics of propaganda in the digital era).

President Trump posted the full video on Facebook and distributed a two-minute excerpt on Twitter.59President Trump’s Facebook Statement, supra note 56. President Trump has generally limited his tweets about the 2020 election to his personal account (@realDonaldTrump) and not his U.S. Government account (@POTUS). See Bobby Allyn & Tamara Keith, Twitter Permanently Suspends Trump, Citing ‘Risk of Further Incitement of Violence’, Nat’l Pub. Radio (Jan. 8, 2021, 6:29 PM), https://www.npr.org/2021/01/08/954760928/twitter-bans-president-trump-citing-risk-of-further-incitement-of-violence [https://perma.cc/YF4C-GP6P] (summarizing President Trump’s use of Twitter to disseminate misinformation during his presidency, ultimately resulting in a permanent ban of his personal account). He tweeted a 2:12 minute excerpt from the beginning of the Facebook video. Trump Twitter Archive, Trump Archive, https://www.thetrumparchive.com/ [https://perma.cc/YLS4-AE9A] (displaying Trump’s tweeted video at item number 726). As of December 17, the tweet had been retweeted 91.6K times and had been viewed 3.5 million times. Id. Later the same day, President Trump retweeted a shorter excerpt of the video from Breitbart News. Id. As of December 17, it had been retweeted 48.5K times and had 993.6K views. Id. Since publication began on this Response, former President Trump’s posts have been deleted from Twitter. Citations are made to the Trump Archive in its place and support for all view count and retweet assertions are on file with the Law Review. The National Archives and Records Administration plans to upload President Trump’s Twitter content in the near future at, Archived Social Media, Nat’l Archives: Donald J. Trump Presidential Libr., https://www.trumplibrary.gov/research/archived-social-media. Both of the companies left the video available for viewing but both attached disclaimers to it.60President Trump’s Facebook Statement, supra note 56; Trump Twitter Archive, supra note 59. The Facebook disclaimer stated: “Both voting by mail and voting in person have a long history of trustworthiness in the US. Voter fraud is extremely rare across voting methods. Source: Bipartisan Policy Center.”61President Trump’s Facebook Statement, supra note 56. The label is visible only on the post that embeds the video; if the user watches the Facebook video in full screen mode the label is not visible. Id. Twitter’s disclaimer refuted the video’s content more directly. It stated: “This claim about election fraud is disputed.”62Trump Twitter Archive, supra note 59.

If Facebook down-ranked President Trump’s video, it did not disclose this publicly. Some of the tools that Facebook could have used to limit the reach of the video include reducing its appearance in users’ News Feeds63See An Update to How We Address Movements and Organizations Tied to Violence, Facebook (Jan. 19, 2021, 8:12 PM), https://about.fb.com/news/2020/08/addressing-movements-and-organizations-tied-to-violence [https://perma.cc/9C6L-VRYM] (announcing downranking as a strategy to mitigate QAnon contents’ reach). and redirecting searches for terms related to the video to other sources.64See Facebook Newsroom (@fbnewsroom), Twitter (Oct. 22, 2020, 3:58PM), https://twitter.com/fbnewsroom/status/1319367628331323392 (announcing that Facebook would redirect users who input search terms related to QAnon to credible resources from the Global Network on Extremism and Technology (GNET)).

As of December 17, 2020, the full video had been viewed on Facebook more than 14 million times; a short excerpt circulated on Twitter had been viewed more than 3.5 million times.65Donald J. Trump, Facebook (Dec. 2, 2020), https://www.facebook.com/DonaldTrump/videos/?ref=page_internal [https://perma.cc/X9SR-MMKA]; Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump), Twitter (Dec. 2, 2020), https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1334240039639937026. This is millions of fewer views (after more than two weeks) than the Breitbart video touting hydroxychloroquine had received in a matter of days in July.66See Darlene Superville & Amanda Seitz, Trump Defends Disproved COVID-19 Treatment, AP News (July 28, 2020), https://apnews.com/article/ap-top-news-malaria-understanding-the-outbreak-health-media-80130998284858a7b73c997e76677137 (noting that a single version of Breitbart’s hydroxychloroquine video had received 17 million views). This suggests that platform curation strategies may have played a role in limiting the reach of—and therefore the number of Americans who watched—the video.

Though Facebook left the video up and gave it only a weak label, the institutional press—including major newspapers—declined to link to the video online and downplayed the speech in their news coverage.67For example, the L.A. Times buried coverage of the video in an article about “chaos” created by President Trump. See Megerian, supra note 55 (discussing President Trump’s threat to veto the defense spending bill before discussing the video). CNN, the cable network, refused to air the speech.68See Chris Cillizza, 46 Minutes that Prove How Dangerous Donald Trump Is to Democracy, CNN (Dec. 3, 2020, 2:16 PM), https://www.cnn.com/2020/12/03/politics/donald-trump-speech-46-minutes-election-fraud/index.html [https://perma.cc/8FP3-4NRB] (providing the rationale behind CNN’s decision to not broadcast Trump’s speech). Rather than debunk content from the speech, news outlets simply refused to give it coverage or to engage with the ideas it expressed. Filled with falsehoods, the 46-minute diatribe was one of the most extraordinarily anti-democratic speeches ever given by a modern U.S. President.69See, e.g., Philip Bump, The Most Petulant 46 minutes in American History, Wash. Post (Dec. 2, 2020, 9:17 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/12/02/most-petulant-46-minutes-american-history (warning that President Trump may endorse stepping outside of constitutional boundaries to achieve electoral victory). For this reason, the video was certainly “newsworthy,” and the press’s refusal to give it much coverage is especially interesting.

On January 6, a mob of pro-Trump insurgents attempted to take over the U.S. Capitol to stop the certification of electoral college votes establishing Joseph Biden Jr., as the winner of the presidential election.70Nicholas Fandos & Emily Cochrane, After Pro-Trump Mob Storms Capitol, Congress Confirms Biden’s Win, N.Y. Times (Jan. 6, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/06/us/politics/congress-gop-subvert-election.html?searchResultPosition=7. In the preceding weeks, President Trump himself and pro-Trump activists had used social media to spread word of upcoming action on that date.71David Jackson & Matthew Brown, ‘Wild’ Protests: Police Brace for Pro-Trump Rallies when Congress Meets Jan. 6 to Certify Biden’s Win, USA Today (Jan. 4, 2021, 5:33 PM), https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/12/31/elections-protest-dc-police-brace-donald-trump-demonstrators/4097472001 [https://perma.cc/A42U-M5F4]. One analysis found that the phrase “Storm the Capitol” was used 100,000 times on social media in the preceding month.72Dan Berry et al., ‘Our President Wants Us Here’: The Mob that Stormed the Capitol, N.Y. Times (Feb. 13, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/09/us/capitol-rioters.html; see also Kate Conger, Mike Isaac & Sheera Frenkel, Twitter and Facebook Lock Trump’s Accounts After Violence on Capitol Hill, N.Y. Times (Jan. 14, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/06/technology/capitol-twitter-facebook-trump.html (“On Facebook, protesters had openly discussed what they aimed to do in Washington on a Facebook page called Red-State Secession for weeks. The page had asked its roughly 8,000 followers to share addresses of perceived ‘enemies’ in the nation’s capital, including the home addresses of federal judges, members of Congress and prominent progressive politicians.”). Watchdog groups noticed the surge in social media content promoting a January 6 assault on the Capitol and issued warnings, but neither Facebook nor Twitter removed “Storm the Capitol” content.73See Katie Paul, Elizabeth Culliford & Joseph Menn, Analysis: Facebook and Twitter Crackdown Around Capitol Siege is Too Little, Too Late, Reuters (Jan. 8, 2021, 4:01 PM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-hate-analysis/analysis-facebook-and-twitter-crackdown-around-capitol-siege-is-too-little-too-late-idUSKBN29D2W5 (explaining how tweets stating that the “Storm [was] upon us” got thousands of retweets and Facebook groups—with thousands of followers—calling for secession were only removed after the January 6 riots).

On the afternoon of January 6, 2021 insurgents stormed the Capitol building, leading to the deaths of five people, including a Capitol Police officer.74See, e.g., supra note 20 and accompanying text; Brakkton Booker, Lawmakers Honor Slain Capitol Police Officer Brian Sicknick in Rotunda, Nat’l Pub. Radio (Feb. 3, 2021, 10:20 AM), https://www.npr.org/sections/insurrection-at-the-capitol/2021/02/03/963598638/lawmakers-honor-slain-capitol-police-officer-brian-sicknick-in-rotunda [https://perma.cc/XQQ9-MFRH]. President Trump produced a short video and posted it to Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube.75See, e.g., Nick Niedzwiadek, Trump Urges ‘Special’ Capitol Rioters to ‘Go Home Now’, Politico (Jan. 6, 2021, 5:04 PM), https://www.politico.com/news/2021/01/06/trump-addresses-capitol-rioters-455607 [https://perma.cc/SL5C-TAGW]. The video did two things: it asked rioters to stand down and reaffirmed the central claim of President Trump’s post-election rhetoric, that the election had been stolen from him.76Conger et al., supra note 72. Twitter gave the tweet that embedded the video this label: “This claim of election fraud is disputed, and this tweet can’t be replied to, Retweeted, or liked due to a risk of violence.”77Ahiza Garcia-Hodges et al., Facebook and Twitter Lock Trump’s Accounts After Posting Video Praising Rioters, NBC News (Jan. 6, 2021, 7:24 PM), https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/social-media/facebook-youtube-twitter-remove-video-trump-amid-chaos-capitol-n1253157. Facebook and YouTube removed the video,78Id. followed by Twitter, which stated that “on balance we believe it contributes to rather than diminishes the risk of ongoing violence.”79Id. Around 7 p.m., Twitter “required the removal” of three tweets by President Trump;80Twitter Safety (@TwitterSafety), Twitter (Jan. 6, 2021, 7:02 PM), https://twitter.com/TwitterSafety/status/1346970430062485505. it later suspended President Trump’s @realDonaldTrump account.81See Allyn & Keith, supra note 59. Facebook suspended President Trump from posting for twenty-four hours.82Conger et al., supra note 72. According to the New York Times, “[a]fter Twitter locked Mr. Trump’s account late Wednesday, Mr. Zuckerberg approved removing two posts from the president’s Facebook page . . . . By that evening, Mr. Zuckerberg had decided to restrict Mr. Trump’s Facebook account for the rest of his term—and perhaps indefinitely.”83Isaac & Conger, supra note 21. Twitter lifted its ban the next day, and President Trump used the opportunity to post a nearly three-minute-long video. Id. On January 8, Twitter permanently banned President Trump’s @realDonaldTrump account. Other social media platforms also shut down Trump’s accounts in the days following the January 6 insurgency. These include Instagram—which is owned by Facebook—Snapchat, and Twitch. See Andrew Ross Sorkin et al., The Deplatforming of President Trump, N.Y. Times (Jan. 8, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/business/dealbook/trump-facebook-twitter-deplatforming.html?.

II. Lessons from the Walk-Back

Professor Thai argued that Facebook’s choice to treat politicians’ speech differently from the speech of non-politicians raised free-speech concerns.84See generally Thai, supra note 1. As a private company controlling a major online platform, Facebook shaped information flows to millions of Americans before and after the 2020 election. There can be little doubt that Facebook’s decisions about how to regulate speech on its platform implicated “free speech” as the concept is understood by ordinary Americans, millions of whom used Facebook on a daily basis in the months before the election.85Facebook, Inc., Quarterly Report (Form 10-Q), at 31 (Oct. 29, 2020), https://www.sec.gov/ix?doc=/Archives/edgar/data/0001326801/000132680120000084/fb-09302020x10q.htm (Facebook had 196 million Daily Active Users in North America in September 2020).

In the period from May to December 2020, Facebook became increasingly hands-on about regulating politicians’ speech.86See supra note 5 and accompanying text. Ironically, when Facebook finally silenced President Trump with an indefinite ban, its decision may have been motivated partly by the concern that his political notoriety—his success as a politician—was the problem, because it amplified the effects of his speech. The political impact of President Trump’s speech made it a liability for Facebook. In the end, despite the company’s early pronouncements, election to the highest office in the United States did not protect President Trump from Facebook’s content-based axe. Or, perhaps it was the loss of the 2020 election that cost him that protection, even while he finished out his first term of office.

Facebook has not disclosed much about the reasoning behind its policy change, especially considering how strongly it once celebrated its hands-off policy. Since Facebook is not a state actor, it is exempt from the sort of judicial scrutiny that would require it to publicly identify the interests served by its rules. As a result, we can only guess about the company’s motives.

Was there ever any bona fide reason to treat politicians’ speech differently from the speech of other users? Doing so might let voters receive candidates’ speech free from third-party filters, perhaps improving the quality of information they can use to make voting decisions, which is good for democracy, while simultaneously increasing trust in the platform companies that turn their filters off, which is good for those companies’ business. (Of course, as I discuss below, it might not be true that transmitting an unfiltered stream of candidates’ speech improves voters’ information).

Separately, citizens might benefit when platforms take a hands-off approach to the speech of elected officials. The speech of a public officeholder might shed light on the workings of government itself. Mark Zuckerberg suggested as much when he defended Facebook’s treatment of President Trump’s statements about the Black Lives Matter protests in May 2020. And, as Professor Thai pointed out, the elected officials “whom Facebook frees from the constraints of its speech code and fact checking, and to whom it sells the keys to its ad targeting kingdom,” hold power over the company and “could wield that authority in ways that threaten its existence.”87See Thai, supra note 1, at 1685. At the time that Professor Thai published his Article, President Trump was Facebook’s top spender on political advertisements.88See Simon Dumenco & Kevin Brown, Here’s what Trump and Biden have Spent on Facebook and Google Ads, AdAge (Oct. 30, 2020), https://adage.com/article/campaign-trail/heres-what-trump-and-biden-have-spent-facebook-and-google-ads/2291531 [https://perma.cc/2RKK-H7CP] (reporting that “Trump ha[d] edged out Biden in terms of Facebook spending” by almost four million dollars as of April 2020). Post-election results show that this trend continued; between January 1, 2019 and Election Day 2020, President Trump, the losing candidate, spent more on Facebook ($115 million) than his opponent, Joseph Biden, the winner, did ($106 million).89Facebook Ad Library Report, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/ads/library/report (providing spending totals for the presidential campaigns through Election Day).

Professor Thai’s suggestion that Facebook designed its speech rules to give special protection to people wielding power over it appears particularly incisive in light of subsequent events. As President Trump’s electoral prospects dimmed in the lead-in to the November election, the company increased its regulation of his speech. And Facebook only de-platformed him after he had lost the election, when his political power was weak.

One of the big take-aways of the events of January 2021—the narrative likely to make it into the history books—is that Facebook’s lax controls made it possible for President Trump to use Facebook’s platform to cause harm and to foment real-world political violence. President Trump proved willing to post harmful content: false information about public health, thinly-veiled racist statements, manipulative and self-serving claims about mail-in voting, and, after the election, blatant lies designed to undercut the legitimacy of his successor’s presidency.90See generally Marianna Spring, Trump Covid Post Deleted by Facebook and Hidden by Twitter, BBC (Oct. 6, 2020), https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-54440662 [https://perma.cc/N69B-LX2X] (quoting President Trump as saying the flu is something America “learned to live with . . . just like we are learning to live with COVID, in most populations far less lethal!!!”); Bobby Allyn & Colin Dwyer, Facebook and Twitter Remove ‘Racist Baby’ Video Posted by President Trump, Nat’l Pub. Radio (June 19, 2020, 10:40 AM), https://www.npr.org/sections/live-updates-protests-for-racial-justice/2020/06/19/880805065/twitter-flags-video-shared-by-trump-as-manipulated-media [https://perma.cc/B4FS-D57P] (reporting that President Trump shared a post containing a doctored CNN headline stating “Terrified toddler runs from racist baby”); Taylor Hatmaker, On Facebook, Trump’s Next False Voting Claim Will Come with an Info Label, TechCrunch (July 16, 2020), https://techcrunch.com/2020/07/16/facebook-voting-label-elections-politicians [https://perma.cc/BQ6N-FRG4]; Elizabeth Dwoskin & Rachel Lerman, ‘Stop the Steal’ Supporters, Restrained by Facebook, Turn to Parler to Peddle False Election Claims, Wash. Post (Nov. 13, 2020, 1:26 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2020/11/10/facebook-parler-election-claims. He was even willing to use Facebook to drum up support for a violent insurrection.91See Elizabeth Dwoskin, Facebook’s Sandberg Deflected Blame for Capitol Riot, but New Evidence Shows How Platform Played Role, Wash. Post (Jan. 13, 2021, 3:27 PM), https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/01/13/facebook-role-in-capitol-protest. When faced with a politician willing to make irresponsible and false claims, Facebook’s speech code not only failed as ground rules for healthy discourse, but also contributed to and amplified anti-democratic rhetoric and incitement, thereby inflicting harm. Facebook underestimated the potential for a politician to use its platform to undermine the public interest and to swiftly escalate posts into real-world physical violence.

Professor Thai wrote that Facebook’s hands-off approach to politicians’ speech could not withstand First Amendment scrutiny.92Thai, supra note 1, at 1679, 1681. To be clear, Professor Thai did not allege that the First Amendment actually limits the ability of a private company to regulate speech. Id. Like many scholars, including myself, he treated First Amendment values and doctrine as a useful frame for understanding how the company’s speech regulation conforms to American ideas of free speech. See, e.g., Nabiha Syed, Real Talk About Fake News: Towards a Better Theory for Platform Governance, 127 Yale L.J.F. 337, 338 (2017) (“The First Amendment shapes how we imagine desirable and undesirable speech. So conceived, it becomes clear that our courts are not the only place where the First Amendment comes to life.”). He described Facebook as “labeling and throttling” content in connection with its fact-checking processes and argued that this, on top of the company’s microtargeting strategies and basic Community Standards, amounted to censorship of the news.93Thai, supra note 1, at 1681. While I do not agree that such strategies amount to censorship, which I would define as the complete removal of speech, I take him to mean that these acts suppress speech in ways that virtually assure that some people will never see it.

Professor Thai raised the concern that Facebook’s exemption of politicians’ speech from its content-based rules “creates a two-tier speech platform that . . . ‘treats people who aren’t politicians as second-class citizens,’”94Id. at 1682 (quoting Gilad Edelman, How Facebook Gets the First Amendment Backward, Wired (Nov. 7, 2019, 5:28 PM), https://www.wired.com/story/facebook-first-amendment-backwards [https://perma.cc/4878-F5ZT]). amplifying the “powerful” speech advantages already enjoyed by national politicians. Is popular sovereignty meaningful in a community in which political leaders comprise a peerage with enhanced rights? Professor Thai’s insight is important: any bright-line distinction between “politicians” and the rest of us is anti-democratic. It habituates us to political discourse in which the interests of those with less political power are functionally subordinated to those with more of it. Since one’s political stature can be enhanced by wealth or corporate political support—without electoral success—the two tiers reinforce some of the most unpopular and plutocratic aspects of our existing political system. If content-based rules restrict your speech on Facebook, but not the next person’s, why bother speaking on a controversial topic at all? Let the politician speak, and “like” or amplify that person’s voice. Instead of expressing yourself, which takes thought, initiative, and risk, you can play a different, more passive role in discourse, up-ranking or down-ranking the speech of other, more important actors. It is hardly democracy in action, but it is commerce in action. After all, Facebook and other social media companies derive value from data about your behavior—how long you spend reading a post, for example—even if you never pen a sentence.

Professor Thai also argued that the two-tier approach “promote[d] a race to the bottom in which willing [politicians] may take the low road of spreading lies that . . . [are] politically advantageous.”95Id. Along this line, Steven Levy, of Wired magazine, has argued that a policy that expressly allows politicians—and no one else—to lie may reinforce longstanding mistrust of politicians as liars.96See Steven Levy, Social Media’s Dance with Donald Trump Is Getting Clumsier, Wired (Nov. 6, 2020, 9:00 AM), https://www.wired.com/story/social-medias-dance-with-donald-trump-is-getting-clumsier [https://perma.cc/QK8L-G2FM] (“It’s almost as if candidate disinformation is automatically factored into our elections these days.”). In other words, the “two-tier” approach itself might undermine American’s faith in their democratically elected representatives. These are powerful arguments and, if they are right, the informational benefits of the two-tier approach to voters or citizens may be offset by the drawbacks.

Facebook’s policy reinforced the idea that politicians’ speech has special importance—that it is worthier of users’ attention than ordinary people’s speech. The institutional press has always “covered” politicians’ speech, as well as the speech of business and civic leaders, with an intensity that it does not give to the expressions of ordinary citizens.97See Thai, supra note 1, at 1645. “Vox pop” or “man-on-the-street” coverage used to be a staple of journalism, but increasingly has been replaced with embedded Tweets.98See Heide Tworek, Tweets Are the New Vox Populi, Colum. J. Rev. (Mar. 27, 2018), https://www.cjr.org/analysis/tweets-media.php [https://perma.cc/QR9V-K5UH] (giving a history of the rise and fall of “vox populi” coverage and describing the recent replacement of “vox populi” coverage with embedded Tweets); Edward Schumacher-Matos, Election 2: To Kill the ‘Man on the Street,’ Nat’l Pub. Radio (Nov. 1, 2012, 3:24 PM), https://www.npr.org/sections/publiceditor/2012/11/01/164107070/election-2-to-kill-the-man-on-the-street [https://perma.cc/A2B8-WFFN]. (Ironically, a 2012 NPR poll found that many Americans felt that “vox pop” features “take time and space away from more valuable analysis and fact-checking”).99Schumacher-Matos, supra note 98. But press coverage of politicians’ speech has always offered context, interpretation, and often pushback to the speech of candidates and elected officials. Unlike social media platforms, which function as speech conduits, the institutional press has utilized a more active approach in transmitting the speech and ideas of politicians to the public.

Professor RonNell Andersen Jones has argued that the President of the United States has an obligation to engage with journalists, particularly over contested matters, as part of a “constitutional system of dialogue between the press and the executive.”100RonNell Andersen Jones, The Press and the Expectation of Executive Counterspeech, 83 Mo. L. Rev. 939, 942 (2018). Instead of publishing the President’s statements word-for-word, journalists interact with the President, framing and asking questions of him or her, in a process that serves both to challenge the President’s positions and to clarify and present the President’s ideas to the public. We hear often about how politicians can use social media to speak “directly” to the people, without the intermediation of the press, and how this is a good thing.101See, e.g., Stefan Stieglitz & Linh Dang-Xuan, Social Media and Political Communication—A Social Media Analytics Framework, Soc. Network Analysis and Mining (2014) (analyzing the impact of direct political speech on social media as active participation in the conversation). Less attention has focused on the Trump administration’s shift away from dialogue with the press in favor of unilateral statements delivered via social media, a shift that served to insulate the President from direct interaction with a corps of experienced White House reporters. The decision by Facebook and other companies to start regulating politicians’ speech represents a new phase in the evolution of social media—one in which these companies will potentially step into a new, mediating role alongside the institutional press.102See Tim Blake Nelson, The Power to Change What We Are: Social Media as the New ‘Fifth Estate’, Hill (Mar. 7, 2021, 1:30 PM), https://thehill.com/opinion/technology/541990-the-power-to-change-what-we-are-social-media-as-the-new-fifth-estate [https://perma.cc/N2QH-CPNW] (arguing that the “immense and perhaps unsurpassed power [social media companies] wield” makes them the “Fifth Estate”). Importantly, of course, social media companies are governed by different ethics and incentives than press companies. For example, they are incentivized to preserve their access to users’ data on a near-constant basis.

Down-ranking, which has become a favored tactic of social media companies to combat false and divisive content, has not been the subject of sustained scholarly analysis. Down-ranking is unique to social media because of the platforms’ ability to covertly amplify or throttle users’ speech; it has no real antecedent in the history of speech regulation. It is a relatively new strategy on social media, and probably does not date back much further than 2015.103See Haan, supra note 41, at 22–23 (elaborating on the inception of Facebook’s policy to manipulate News Feeds through down-ranking).

When it comes to democratic deliberation, down-ranking may be the most dangerous tool that social media companies wield. Thus, it is particularly interesting that, in 2020, Facebook gave up its previously generous treatment of politicians’ speech in favor of down-ranking strategies that lacked user transparency. Free speech advocates will focus on burdens to speakers and listeners—how a speaker cannot know whether posts are being down-ranked and how a listener might miss down-ranked content that is informative. But there is also an interesting story here about democratic dialogue—how Facebook’s choice to curate politicians’ speech, rather than simply remove it, shapes political discourse. Until recently, our democratic system had relied upon a robust institutional press with a constitutionally-contemplated role in publicly dialoguing with and challenging the President’s speech. Social media platforms initially seemed to offer politicians a way to circumvent the press and speak, without a filter, directly to the People. But that short-lived regime is over.104See supra note 100 and accompanying text (explaining the traditional system of dialogue between the executive and the press). Even if Facebook’s Oversight Board restores President Trump’s account, that account will be subject to curation strategies that Facebook applies to politicians’ speech. Down-ranking is the next major front in platform regulation of politicians’ speech.

Conclusion

Professor Thai’s Article, Facebook’s Speech Code and Policies: How They Suppress Speech and Distort Democratic Deliberation, highlights the need to think more cogently about how the surveillance capitalism business model distorts democratic deliberation. This Response has shown that although Facebook pivoted after the publication of Professor Thai’s Article and changed its approach to politicians’ speech, the concerns Professor Thai raised in his Article remain. Facebook’s decision to treat politicians’ speech differently from the speech of ordinary Americans proved unworkable in the Trump era and Facebook ultimately walked back its much-trumpeted “hands off” approach. We are entering a new era in which we must grapple head-on with the reality that platform companies regulate politicians’ speech, in obvious ways and through less-obvious methods of curation.